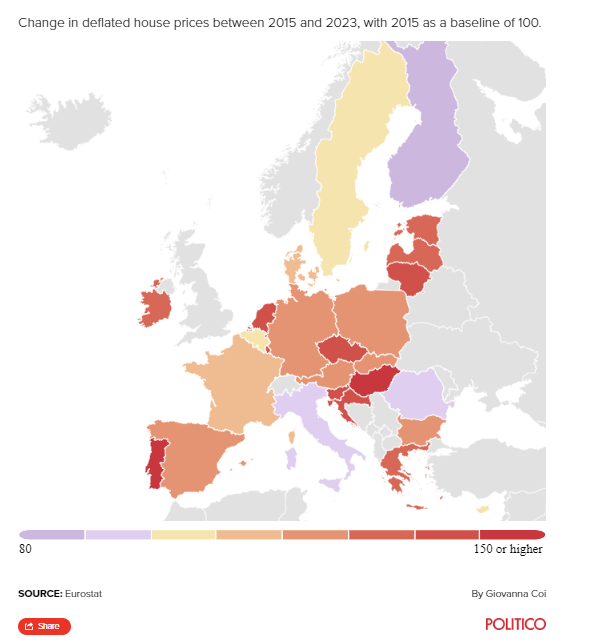

Europeans’ anger overflows over lack of affordable housing – In cities including Lisbon, Amsterdam and Milan, thousands of protesters have taken to the streets to denounce the lack of affordable housing

From Lisbon to Łódź, European anger is overflowing over the lack of affordable housing.

In cities like Lisbon, Amsterdam and Milan, thousands of protesters have taken to the streets to denounce the lack of affordable housing. Last fall, anti-immigration protests erupted in Dublin fueled in part by allegations that the Irish capital’s limited public housing was being given to foreigners.

In a poll ahead of the far-right surge in the European elections, mayors of major cities cited housing as one of the biggest issues facing their constituencies.

“We have reached the tipping point of a situation that has been in slow decline for years,” said Sorcha Edwards, secretary general of Housing Europe, which represents public, co-operative and social housing providers.

“For a long time, politicians were happy to ignore the issue because it affected low-income groups, but now it affects people who consider the offspring of the middle class and even the middle class itself,” he said.

Europeans spend on average almost 20% of their disposable household income their.

“We’ve been warning about this issue for at least 10 years, but politicians were willing to ignore it until recently when it came back on the agenda,” Edwards said. “Years of inactivity have now been compounded by rising inflation and rising mortgage prices that have brought private sector construction to a standstill.”

Edwards also emphasized that the characteristics of the housing crisis differed from city to city.

“In tourist locations, for example, there is the added pressure caused by Airbnb and other short-term rental platforms, but the core issue remains the same,” he said. “The decision by local and national authorities to stand back and not act on housing has brought us to this point.”

Organized Denmark

But some countries are better organized than others to handle the crisis.

In Denmark, public housing is managed according to a national model. Housing associations are not run for profit and two-thirds of the rent collected goes to a national building fund, which has been used since 1967 to finance the construction of new homes and the renovation of existing ones. The fund also supports health, employment and social initiatives in disadvantaged areas across the country.

Bent Madsen, CEO of the Danish Association of Non-Profit Housing Providers, said that although around a quarter of the housing was allocated to vulnerable groups – such as single-parent families or refugees – anyone could apply for housing, regardless of income.

Around 965,000 people, or one sixth of Denmark’s population, lived in social housing as of 2022. The public housing sector is the second largest provider in the country, with almost 600,000 dwellings, equivalent to one fifth of the national building stock .

The fact that the system is designed to be not-for-profit makes social housing much more affordable than its counterpart in the private sector. For public housing built after 2000, the rent per person per square meter is 40% cheaper than market prices, according to data analyzed by the Danish Federation of Non-Profit Housing Providers.

Swiss bliss

In Switzerland, many cities face the worst storm thanks to the non-profit cooperative houses Genossenschaften.

The aim of Swiss housing cooperatives is to provide affordable, sustainable and communal living. Because they are not-for-profit businesses, they offer housing that is, nationally, an average of 15% cheaper than comparable rents.

Rebecca Omoregie, vice president of Wohnbaugenossenschaften Schweiz, an association of non-profit housing developers, said the cooperatives are democratically organized, with all residents having equal rights even in managing the buildings.

“They are not state-subsidized social housing, which means there are no mandatory income and property requirements,” he explained, adding that the properties are available to everyone. “However, the [συνεταιρισμοί] they ensure a good social mix and the majority apply occupancy regulations.’

in Zurich, around 7% of housing is now council owned — but almost 18% of apartments in the city are Genossenschaften, offering rental prices on average 45% cheaper than their for-profit counterparts. This mix helps maintain affordable housing in one of Europe’s most expensive cities.

Omoregie said the Zurich government had helped the co-operative housing model become successful by buying land for such housing in the first half of the 20th century and further supports the model with reduced capital requirements.

However, despite the Genossenschaften model, Zurich has been hit by the housing crisis. New housing construction has not kept pace with the arrival of migrants from European Union countries and rents for new tenants have risen by 30% since 2016.

“Cooperatives are struggling to expand because there is hardly any land on the market and the prices of the remaining land have risen to levels that make it impossible to build affordable housing,” Omoregie said.

“As a result, most of the increase in Zurich’s co-op housing stock is due to the replacement of existing housing with larger buildings.”

Source :Skai

With a wealth of experience honed over 4+ years in journalism, I bring a seasoned voice to the world of news. Currently, I work as a freelance writer and editor, always seeking new opportunities to tell compelling stories in the field of world news.