Paris climate targets won’t halt sea-level rise, new study finds

One of the effects, perhaps the most serious at the present time, of global warming, is the rapid rise in ocean levels. In the past, dozens of studies have provided an order of magnitude of the problem. Now, with cross-referenced information from various sources, environmentalists are able to draw more specific conclusions.

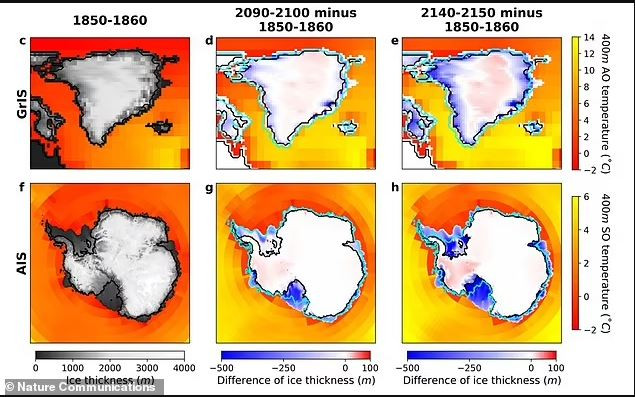

Scientists have calculated the volume of water that will be released into the sea, from the melting of the ice in Antarctica and Greenland. These two regions have, in frozen form, 99% of all fresh water that exists on the entire planet.

Average global sea levels have already risen by about 20 centimeters over the past century, and that trend is likely to accelerate with global warming, researchers say.

The new study was led by Jun-Young Park at Pusan National University in South Korea and Fabian Schloesser at the University of Hawaii.

“With a significant proportion of the world’s population living near coasts, it is vital to provide accurate predictions of global and regional future sea-level trends,” they say in their paper, published in Nature Communications.

“Our results demonstrate that estimates of future sea-level rise fundamentally depend on the complex interactions between ice sheets, icebergs, the ocean and the atmosphere,” they emphasize.

Although melting ice from the two ice sheets is not the only cause of sea level rise, they are believed to be the largest sources.

These modeling scenarios from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) show different ways the world could change and are often used by researchers.

The five scenarios range from SSP1-1.9, where CO2 emissions are “very low” and have fallen to net zero around 2050, to the horrendously worst-case scenario SSP5-8.5, where greenhouse gas emissions triple by 2075.

If SSP5-8.5 occurs, the contribution of just the two ice sheets to global sea level rise will be 1.4 meters by 2150.

Unfortunately, the authors found that limiting global warming to 3.6°F (2°C) above pre-industrial levels – a key goal of the Paris Agreement – would be insufficient to slow the rate of global warming sea.

Achieving this goal would not prevent an irreversible loss of large areas of the western part of the Antarctic ice sheet, which is smaller in mass than its eastern counterpart.

Another group of experts has already warned that melting West Antarctic ice could cause sea levels to rise by up to 10 feet.

Only by limiting the rise in global temperatures to below 3.2°F (1.8°C) above pre-industrial levels by the end of this century can accelerating sea-level rise be avoided, warns new study.

Source: Skai

I have worked as a journalist for over 10 years, and my work has been featured on many different news websites. I am also an author, and my work has been published in several books. I specialize in opinion writing, and I often write about current events and controversial topics. I am a very well-rounded writer, and I have a lot of experience in different areas of journalism. I am a very hard worker, and I am always willing to put in the extra effort to get the job done.