The Pantanal will return to prime time on Monday (28), when the new edition of the soap opera, a classic from the 1990s, now made by TV Globo debuts.

The story of Juma Marruá, Jove and José Leôncio was first aired on TV Manchete 32 years ago and was a huge success.

The new edition will tell that story once again, with a new cast — but it’s not just the actors that have changed.

The Pantanal, which is the largest wetland in the world, will appear drier on Globo than on Manchete.

“I had never seen it so dry,” says biologist Edna Scremin-Dias, who is a professor at the Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul and has worked there since 1982.

She says that the months of January and February are the rainy season and that the fields of Passo do Lontra, the region she frequents most, to the south, should be flooded and dotted with ponds.

“The ponds are dry in the middle of March, when the peak of the drought is usually in July, August. Most of the fields did not flood.”

She also got a fright when she saw the Abobral river run out of water. “The river is partially stopped. I had seen the low waters before, but this was the first time.”

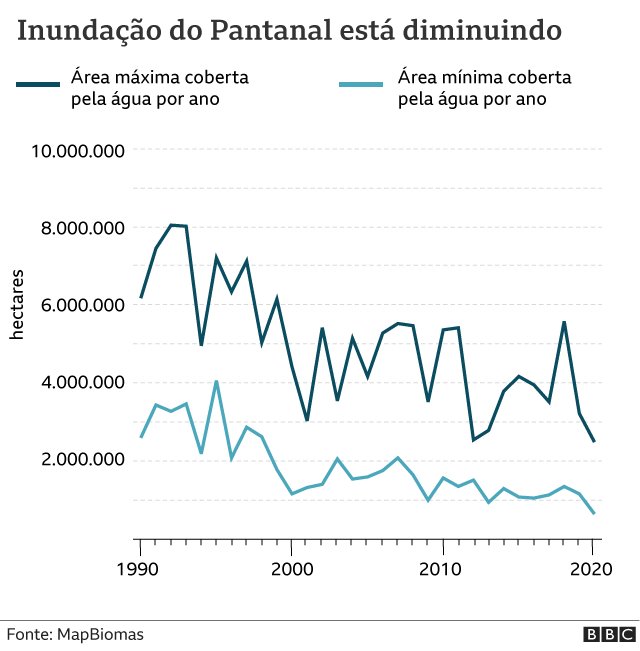

Data and satellite images show that the surface covered by water is significantly decreasing in the Pantanal.

The image above on the left shows in different shades of blue the parts of the Pantanal that were at some point covered by water (its flooded area) in 1990, when the telenovela first aired.

On the right, the area flooded in 2020 — the most recent year of monitoring by the MapBiomas project.

The initiative, a cooperation between universities, companies and NGOs, maps land use changes in Brazil based on computerized analysis of satellite images.

These data show that the historical average of the flooded area of the Pantanal has fallen by 26% in the last 30 years.

The average was calculated by BBC News Brasil based on data from the MapBiomas historical series, which begins in 1985.

The sum of the area covered by rivers and lakes and also the flooded fields and swamps was taken into account. The two together represent the flooded area of the Pantanal.

Eduardo Rosa, responsible for monitoring the Pantanal at MapBiomas, explains that analyzing this entire flood area, rather than just one of the two elements alone, shows better how the water surface has varied in the region.

In turn, the choice for the mean smoothed out the annual fluctuations in the flooding area that are natural in the Pantanal cycle.

There are years when it fills more and in others, less. Therefore, comparing two isolated years does not reflect how much water the Pantanal lost over that time.

But the downward trend is clear in the evolution of both the total and average inundation area over the last 30 years.

“Water gives life back to the Pantanal. The fauna and flora develop, renew themselves, but the Pantanal floods less and less”, says Rosa.

While the maximum area covered by water recorded each year is decreasing, the minimum area is also getting smaller and smaller.

In some of the more recent years in the graph above, the maximum level of flooding was even below the minimum recorded in the early 1990s.

In October last year, the Paraguay River reached the second lowest level in 121 years of measurement in the city of Ladário, in Mato Grosso do Sul — this index even has its own name: ruler of Ladário.

Floods are also getting shorter, says Felipe Dias, executive director of Instituto SOS Pantanal, a nonprofit dedicated to protecting the biome.

“In the past, the Pantanal was flooded for three, four, even five months, today it has decreased to one, two months”, says Dias.

This is especially critical in an ecosystem that has its essence in this back-and-forth of the waters — and which depends on it for its preservation.

Water plays a role in the Pantanal that goes beyond regenerating the ecosystem. Flood is also a natural barrier for man.

Areas that are flooded for a long time are not suitable for livestock or agriculture and maintain these economic activities on the edges of the region.

A drier Pantanal is, therefore, a Pantanal more favorable to the expansion of agriculture – and also more vulnerable to deforestation and fires, which in 2020 caused the biggest environmental tragedy in decades, when 30% of the Pantanal burned.

The image above on the left shows in yellow the area of the Pantanal that was occupied by man in 1990, next to the same image in 2020.

It is possible to see the advance of man over nature in the Pantanal.

Although the Pantanal is considered one of the most conserved biomes in the country, Felipe Dias, from SOS Pantanal, points out that the deforested area in the Pantanal has doubled in the last 30 years.

“The 16% we have today were 8% in the 1990s”, says Dias.

Deforestation includes not only felled trees here, but also places where the native grass of the region’s fields has been replaced by one more suitable for livestock.

The index has been stationary at more or less at this level for the last ten years, says the researcher, but that should change because the last flood in the Pantanal was four years ago.

“With this drought in recent years, I believe that deforestation has increased again. Many exotic plants are being planted instead of native ones, and soy, which is still outside the limits of the swamp, is getting close to the edges”, assesses Dias.

The water that supplies the Pantanal

To understand what is happening in the Pantanal, scientists say it is necessary to look outside it, especially to the Amazon and the Cerrado, where most of the water that floods the Pantanal comes from.

“Rainfall levels are low in the Pantanal, 70% to 80% of the water comes from outside”, says Dias – and less water has arrived there.

Eduardo Rosa, from MapBiomas, points out that one of the reasons lies in the rivers that flow down from the Cerrado plateau.

“The amount of water they bring has decreased because there has been a very large loss of vegetation on the plateau, and this leaves the rivers silted up. There were many rivers and springs that passed over the top to make fields and pasture”, says Rosa.

Another part of the water reaches the Pantanal by air. It is thrown into the air by the trees of the Amazon and is carried by the winds, forming a corridor of humidity known as the flying river, which passes over the Pantanal on its way to southern Brazil.

The signals are not good in this case either, says meteorologist Renata Lisbonati dos Santos, a professor at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, where she coordinates the Laboratory for Environmental Satellite Applications.

The researcher points out that the air humidity in the Pantanal has dropped by 25% since 1980.

“Several studies point out that deforestation in the Amazon altered the water cycle of the forest and affected this flow of moisture. Less moisture may be coming or this moisture may be being directed elsewhere”, says the scientist.

On the other hand, all this may be part of the natural cycle of the Pantanal.

While the most modern monitoring dates back to the 1980s, the data from Ladário’s ruler span more than a century.

They show that there have been periods of drought as intense as now — the last one in the 1960s.

But there is an important difference there: the climate has changed in recent years. The Pantanal became not only drier, but also warmer

Lisbonati points out that the average temperature in the region has increased by just over 2º C in the last 30 years. “It was more than the global average”, says the meteorologist, “but we still don’t know why”.

At the same time, the rains are getting more sparse and intense, which is not ideal. Because the heat causes more water to evaporate from the ground, and for it to flood again, the rains need to be more constant.

“If there’s a rain today and another one only in 20 days, it will take time to get soaked or not even that”, says Felipe Dias.

Thus, everything becomes drier — and with each piece that dries, the Pantanal loses a little of what makes it the Pantanal.