Papyrus dated to the mid-2nd century AD – Muziris, the legendary port of plenty and wealth in India

Valuable evidence about the trade routes that connected the Mediterranean with the lost ancient port of Muziris in India, which, according to the Roman writer Pliny, was its “first trading station” is brought to light by a new study of a Greek papyrus, by EKPA professor Amfilochios Papathoma.

“This unique papyrus is widely dated to the mid-2nd century AD.” Mr. Papathomas tells APE-MPE, “it provides us with valuable testimony about the trade between India and Greco-Roman Egypt – and from there about India’s trade with the rest of the Mediterranean world – during the Roman period”.

Equally important are the conclusions drawn from the study presented by Mr. Papathoma at an Indo-Greek scientific conference held in New Delhi. They demonstrate the manner of payments, contracts, taxation, trade and insurance clauses in force in the heyday of the Roman empire for the valuable goods carried from the rich port of India to Alexandria and vice versa.’

The papyrus, to which scientists gave the name of the legendary Indian port, is today kept in the Austrian National Library in Vienna.

There are two different texts written on the front (recto) and on the back (verso) of the papyrus respectively, a contract and a list of goods imported from India to Egypt. The toponym Mouziris appears here for the first and only time in Greco-Roman papyri” says Mr. Papathomas.

Muziris, the legendary port of India

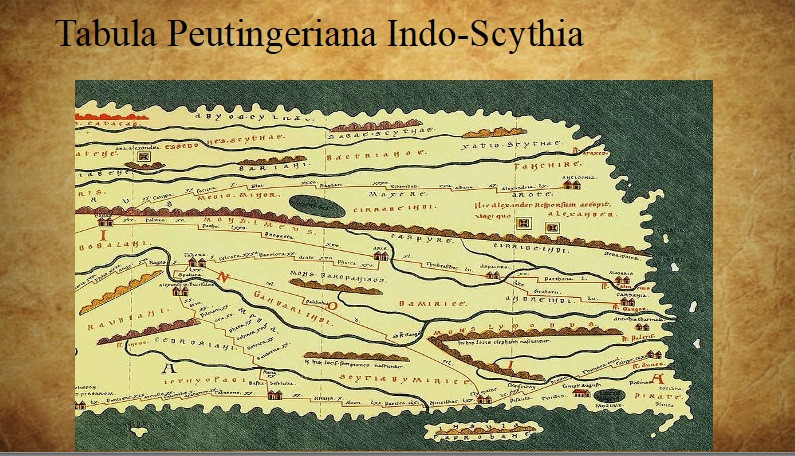

Referring to the historical sources for the port of Muziris, the EKPA professor pointed out that it was a port in southwestern India (present-day Patanam) which was relatively close to Nelkyda (ancient Greek Nelkyda). Place and toponym were already known from Greek and Latin literary sources such as Periplous of the Red Sea, Claudius Ptolemy’s Geography and Pliny’s Natural History. Muziris also appears in the so-called Tabula Peutingeriana, a 13th-century parchment copy of a map from the Roman period, which is also kept in Vienna.”

In recent decades, archaeological research in India has studied several coastal areas in order to provide an answer to the mystery of the exact location of the rich port that flourished for many centuries and was abruptly “erased” from the maps around the 14th century. A.D. However, an area in southern Kerala that is being excavated has recently gathered the greatest possibilities to “hide” the location of this particularly important ancient port of India.

Indian poems and other sources describe a port of abundance and wealth where Western ships landed laden with gold, wine, olive oil and beautiful vessels and departed laden with pepper and other spices, ivory, pearls and especially semi-precious stones that abounded in it but and with silk, the aromatic nard root and products from the eastern Himalayan regions.

Those who studied the Greek text of the papyrus, initially decided that it concerns a contract for a shipping loan, which was concluded in the Indian port, between a shipowner and a merchant, an opinion that ultimately turns out to be rather wrong as it concerns much more and even seems to follow common Mediterranean practices around loans-goods-pledges-insurance just as merchants used them centuries earlier in classical Athens.

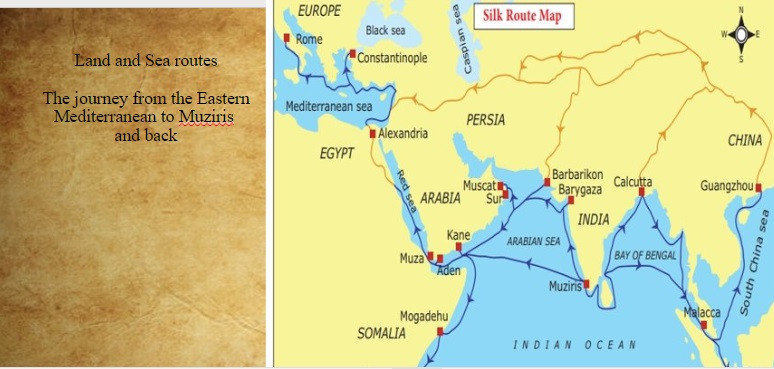

Newer studies have concluded that the contract was not drawn up in the Indian port, but at one of the stations on the Red Sea trade route (probably the port of Berenice). This was also contributed by the correct interpretation of the text which determined that the speaker in the papyrus was trying to secure his funding for the return journey to India but also the payment method for the camel drivers who would carry the goods inland and until loading them to the river (the Nile) and to the riverboat that would then carry them to Alexandria.

The papyrus contract shows the wealth of the port, since it records the shipment of ivory (167 tusks and fragments), cloth and nard weighing 3.5 tons and worth (after a small tax deduction!) 1154 talents and 2852 drachmas (almost 7 million sesterces ).

Sumerians, Harappa and the successors of Alexander the Great

“The Papyrus of Muzireos” estimates Mr. Papathomas “completes a picture of commercial activities in the Red Sea, the Persian Gulf and the wider Indian Ocean that took place as early as the second millennium BC. Since the time of the Sumerian and Harappan civilizations, these areas have facilitated contact between Mediterranean and Middle Eastern societies on the one hand and the eastern and southernmost regions of Asia in the Indian Ocean on the other.

After Alexander the Great his successors kept the trade routes to India open.

“…The Seleucid and Ptolemaic empires, notes the EKPA professor, “founded a colony on Icarus, on the current island of Failaka in Kuwait, and developed trade contacts with the Gerrachian Arabs, who lived in the eastern Arabian peninsula respectively. The Ptolemies also established stations in the eastern desert of Egypt and ports on the coast of the Red Sea. The use of the Red Sea for commercial purposes continued, as evidenced by the many stations established to oversee such activity during the late second and first centuries BC. At the end of the 2nd c. BC, the Greeks, the professor notes, learned to use the monsoon winds to sail the open sea to India. The south-west monsoon enabled traders traveling from the Red Sea ports to depart in July and reach Indian shores around the latter half of September and then, with the north-east monsoons, to start the return journey around the end of December and beginning of January”.

The Romans followed the Greeks who knew how to sail with the monsoon winds

The same trade routes were followed by the Romans when they dominated the region. The Roman empire took over the regulation and taxation of goods entering and leaving Egypt via the Red Sea. The peak of this activity occurred during the first century AD. During the Roman period, and especially in the latter part of the first century, the participation of the Mediterranean in the trade of the Indian Ocean was probably greater than ever before.’

“Our papyrus testifies to a late flourishing of this commercial activity in the Indian Ocean in the 2nd c. A.D. Merchandise from the Mediterranean reached India via Alexandria, the Nile River city of Coptic, which was the major Nile port at about the same longitude as the Red Sea port Myos Ormos, and close to the other major Red Sea port , Berenice” emphasizes Mr. Papathomas.

Thanasis Tsiganas

Source :Skai

I am Frederick Tuttle, who works in 247 News Agency as an author and mostly cover entertainment news. I have worked in this industry for 10 years and have gained a lot of experience. I am a very hard worker and always strive to get the best out of my work. I am also very passionate about my work and always try to keep up with the latest news and trends.