Of Jonathan Teppreman

In 1950, a 22 -year -old immigrant with an unreadable name living in a frozen Canadian city wrote a postgraduate dissertation that predicted the fall of the Soviet Union – and helped implement the strategy that eventually secured its collapse.

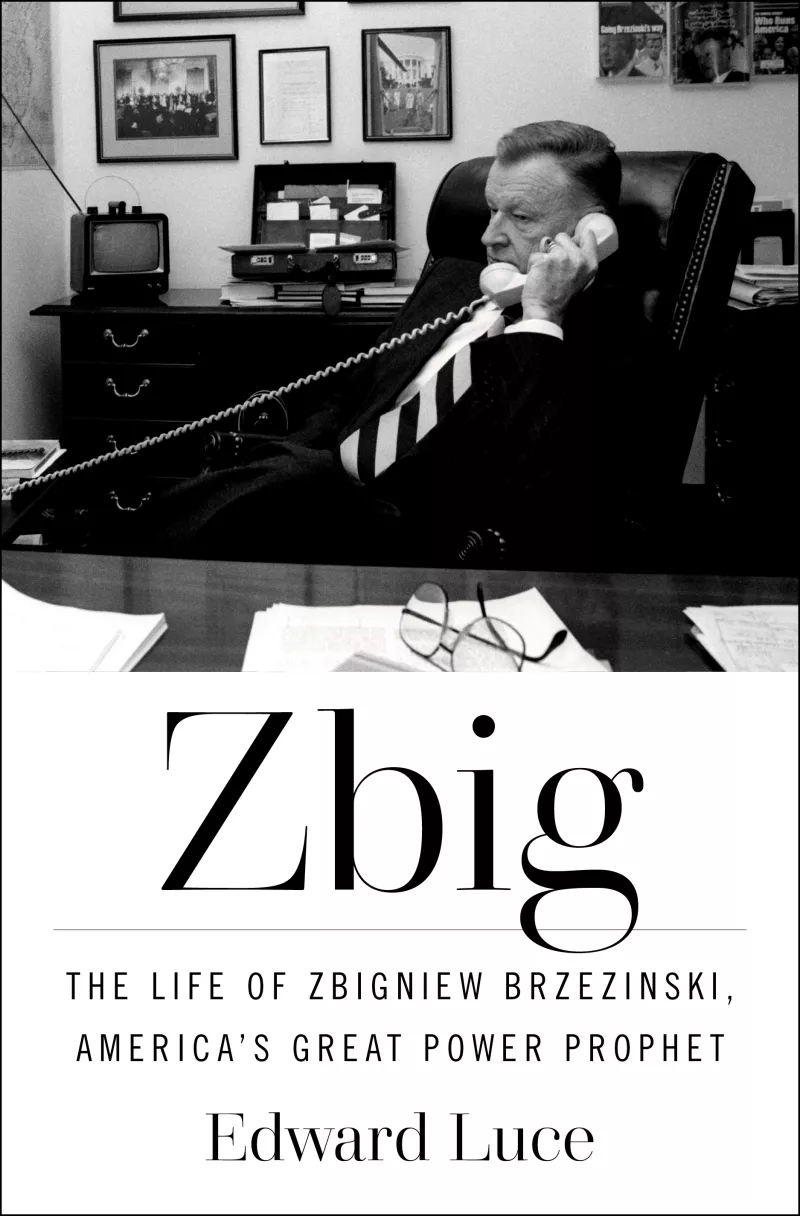

This anecdote is close to the beginning of the book “Zbig: The Life of Zbigni Brezinsky, the Great Prophet of America” (Zbig: The Life of Zbigniew Brzezinski, America’s Great Power Prophet). It is one of the many notable episodes narrated by the author of the book – Edward Lous, the so -called “national author” of the United States and for years of the Financial Times columnist – and is why he wins the title “Prophet” in the subtitle of the book. “Zbig” is the long story of a brilliant Polish immigrant who became the leading Sovietologist in America, then a leading strategy, and then a serial “presidential mentor” – over time he would advise John F. But of all his roles, the most famous was the four years he spent as President Jimmy Carter’s national security adviser.

One of the very strengths of this book is Lus’s decision to organize it as a mental and professional biography. Instead of accurately describing any overthrow of Brezinsky’s life from his birth, the author focuses on his ideas and career, and how the events influenced them.

This does not mean that ‘Zbig’ has no resumes. Those who seek them will find many stories about Brezinsky’s years – his parents were aristocrats of the Habsburg era, excluded in Montreal (where his father served as a diplomat of the interwar) first by fascism. Lus covers the young Brezinsky’s academic triumphs: Having arrived in Canada as a 10 -year -old without speaking English, he won his school’s top school award during his first year and continued his academic career at McGill. We also receive details of his female adolescence, his long marriage with his very patient wife, his financial problems, his famous children and so on. But the biographies exist to serve the largest plot, which is how and why Brezinsky’s strategic thinking developed in the way it was developed.

This emphasis perfectly solves a central problem that all biographers face: how to turn a life, with all randomness, chaotic circumstances and the wrong beginnings, into a coherent story.

It is a very useful context in this case, because Brezinsky’s life was amazing, but the legacy he leaves is complicated. Part of the cause, as Lus puts it, is that while Brezinsky was always deeply faithful to Carter, Washington is a city full of factions, and Brezinsky “had no other race but his own. He did not belong to any recognizable foreign policy school; neither a firm hawk nor a dove. He had some time for labels such as “realist” and “idealist”. ” He often changed his mind and avoided both doctrines and, at times, both major political parties. (Democratic throughout his life, voted for Richard Nixon in 1972 and supported Bush in 1988.) While writing stable books and essays, he was at best a mediocre writer without the “poetic touch of one [Τζορτζ] Hanan or anecdotal vitality of a [Χένρι] Kissinger. “

Brezinsky was also honest, unfiltered and conflicting, known for the sharp attacks that could really hurt. Incorporating the life of his subject, Lus writes, and a few says, that “there was never a phase of a stochastic break when he did not have an easily recognizable and extremely provocative group of enemies.”

Then there was the constant connection of Brezinsky with Kissinger to public opinion. This correlation was probably inevitable, given the strange similarities of the two men. Both were European refugees with a strong accent that came to academia before becoming US National Security Advisors at the height of the Cold War.

But they were also very different, in ways that tended to publicly operate at the expense of Brezinsky. If he was a sharp weapon, Kissinger was the opposite: kind and charming, genius in the manipulation of the media and with a “sphinx” capacity to cover his own views in order to ensure his continued access to power. While the two men frequently communicated and (almost) always maintained heartfelt relationships, Lus records how Kissinger was silently trying to undermine his opponent at almost every step.

Indeed, given Kissinger’s back stabbings and Brezinski’s disgust for social bareness, it is noteworthy that Brezinsky has managed to reach so far and have such a profound impact on US foreign policy. What he did is due to the power of his brain, his perseverance and the intense sense of his mission, which Lus attributes to his “wounded Polish” and to a profound mistrust of Moscow.

Brezinsky was more right than unfair, and in relation to consequent issues: above all, how to peacefully destroy the Soviet Union. Lus’s position is that Brezinsky was able to predict and encourage this result thanks to his discretion in Polish and Russian (who began to study as a teenager), in his deep study of the communist world, in his glittering confidence in the United States and in the United States. As Lous tells, these characteristics led him to the perception that led his career to the Cold War: that the Eastern Bloc was not a monolithic entity that had to be facilitated by the United States – as many scholars believed then – but a divinely divided They were waiting for an opportunity to stand.

This recognition – that the USSR had a “problem of nationalities” that would mean its destruction – may seem obvious today, at this time of emerging nationalism. But they were contrary to conventional wisdom for much of Brezinsky’s career. This never bothered him. He didn’t care much about what others were thinking. And when he became the US foreign policy architect in January 1977, he gave him a weapon he could use with a deadly result. Examples include Carter’s encouragement to improve links with Moscow Satellites (thus gradually encouraging their independence), the use of human rights, which the Soviets had committed to respecting the 1975, 1975, 1975 and a shrewd geopolitical factor made by Pope John Paul II in 1978 (for years, KGB was convinced that Brezinsky had arranged his choice as a Pope.)

“Zbig” is great to read, written with the same simple, clear prose as the columns of Lus. Lus does a great job by rebuilding old political discussions in all their shades, especially during Carter’s term. The upheaval of that time – in four years, the United States normalized relations with China, overseeing a peacekeeping agreement between Israel and Egypt, returned the Panama Canal, saw the Soviets invading the Afghanistan, Homer – They make this part of the book particularly exciting.

If I had to grumble, I would prefer a window to the private, deeper self of Brezinsky, especially as Lous had access to all his diaries, correspondence and other documents. But maybe that was impossible. As Lus repeatedly points out, Brezinsky spent strikingly some time to endoscopy. He may not have a personal life worthy of study.

Although this is not an authorized biography, Brezinsky’s family collaborated with the author and Lus loves his subject indefinitely. But this is not a problem … He does not prevent him from honestly dealing with Brezinsky’s deficiencies (for example, he was infamous “tight” with both money and praise) and his mistakes, especially common errors with Carter on all Iranian issues. It also deepens Brezinsky’s persistently controversial career – the accusation of being against Israel in a way that could touch the limits of anti -Semitism. But Brezinski’s real problem on this issue seems to have been the coarsely wickedness, not prejudice. As Lus shows, his family had a long history of supporting Jews in Poland, and according to Ezer Weiman, Israel’s defense minister in the late 1970s, Carter and Brezinsky did more for the security of the Jewish state than any other US government.

Many events in this book, from the Games in the Middle East to relations with Moscow, coincide with today’s crises. But her era and personalities are also completely different from ours. Perhaps the most striking difference is the long -standing presence of such a deeply educated, dedicated and optimistic intellectual in the heart of US foreign policy design. Brezinsky’s methodicality and his trust in his home country may seem almost graphic on the basis of today’s data, but we could use more of these characteristics and more people like him today.

Jonathan Teppeerman is the editor -in -chief of Catalyst and a senior partner at the George W. Bush Institute. He is a former editor -in -chief of Foreign Policy and CEO of Foreign Affairs, and author of The Fix: How Countries Use Crises to Solve the World’s World Problems.

Source :Skai

I am Frederick Tuttle, who works in 247 News Agency as an author and mostly cover entertainment news. I have worked in this industry for 10 years and have gained a lot of experience. I am a very hard worker and always strive to get the best out of my work. I am also very passionate about my work and always try to keep up with the latest news and trends.