The doctrine of the European Union of the “chosen” and the Greek memoranda – The “flirt” with the chancellery and the theory of balanced state balance sheets

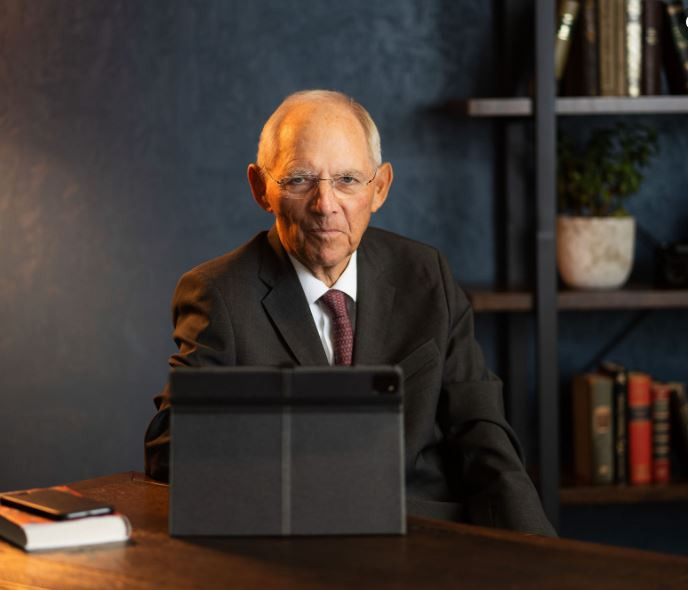

Wolfgang Schäuble never became chancellor – he could, many say. However, he managed to play a decisive role in shaping the history of the Federal Republic of Germany. He sealed an era of tectonic changes in his country and in Europe, a generation of great politicians and a period of critical decisions. And, as is often the case with important figures, not always in a positive way.

We Greeks have the right to be critical of him. At one of the most difficult moments in our recent history, he expressed the most chilling, stern – if not punitive – logic for our country and people.

But Wolfgang Schäuble was German. He was elected in Germany, by German voters, with the mission of safeguarding German interests, faithful to his Protestant principles. Although a staunch Europeanist, he did not believe in the unrestrained expansion of united Europe and always supported the creation of a narrow strong core, with viable and well-established institutions. In this logic, Greece, the European South, its crises and weaknesses, were a brake.

For the Germansinstead, Wolfgang Schäuble was a serious and reliable politician, respected even by his political opponents. His pivotal role in the negotiation of the German Reunification Treaty took on historic characteristics, as did his influence on the subsequent formation of the positions of the Christian Democratic Party (CDU), especially on economic, European and foreign policy issues.

Son of a tax collector from Hornberg, Baden-Württemberg, Schäuble studied law, worked in the tax services and in 1972 was elected to the Bundestag for the first time. In Helmut Kohl’s inner circle, he served as Minister of Special Affairs and then of the Interior and he supported his chancellor even in the “donations scandal” that later sealed the CDU – and ultimately Schäuble’s own career.

The signing of the German Reunification Treaty on August 31, 1990 was the zenith of the then 48-year-old politician’s career. The road to the chancellery now opened before him. This road was blocked on October 12 of the same year, in Openau, a few kilometers from his home. At an open election rally a – as it turned out later – mentally disturbed man approached him and shot him repeatedly. One of the bullets crushed his spine, causing him to become a paraplegic. It was initially doubtful whether he would return to politics. But he faced his disability with the same strong will that we all know and within a few weeks he was back – in a wheelchair now – in his ministerial duties, to determine another historic decision for his country, the return of the capital from Bonn to Berlin.

At the end of 1991, Wolfgang Schäuble was again seeing the road to the chancellorship, espousing a conservatism open to renewal, anchored at the same time in the traditional German values of community and duty—perhaps even national pride, which was still a taboo subject for the country. At the same time, he was fanatically opposed to a hypertrophic state and economic protectionism.

While Helmut Kohl was committed to the European vision, he bore the burden of the internal administration of a country, which was struggling to find a new identity and whose citizens had to reacquaint themselves with each other. In 1998, Helmut Kohl lost the election and the CDU passed into the hands of Wolfgang Schäuble. His first intra-party decision turned out to be rather fatal: appointed Angela Merkel as general secretary of the party.

When it broke out “donation scandal” concerning the Kohl era, the East German turned out to be more “cold-blooded” than he. Wolfgang Schäuble became involved in the case, as he had not submitted a receipt for a donation of 100,000 marks to the party, while Mrs. Merkel was “emptying” the leadership with her newspaper article. Under the weight of the scandal, in February 2000 the Schäuble period at the leadership of the CDU ended, and with it any ambitions for the chancellorship.

In 2004 his name was heard again for the position of Federal President of Germany. Angela Merkel, however, chose the – politically unknown – head of the IMF, Horst Keller, confirming the difficult relationship between them.

The following year Wolfgang Schäuble returned to government as interior minister in the first Merkel government. Through his hands passed the establishment of the German Islamic Conference and the new immigrant integration policy. From his mouth it was heard for the first time that “Islam is now an inescapable part of Germany and Europe”. He simultaneously promoted the introduction of biometric data in passports, the creation of an anti-terrorist service and the return of the armed forces to operations within Germany as well. In 2009, the Federal Ministry of Finance welcomed its most iconic tenant to date. Under his guidance, the German government presented and implemented balanced budgets – for the first time since 1969.

The Greek crisis

Given Wolfgang Schäuble’s worldview and path, it was no surprise the attitude he maintained during the crisis in the Eurozone and especially towards Greece. He believed that the country should leave – at least temporarily – the single currency zone, to implement extensive structural reforms and to proceed with a deep consolidation of its finances.

Fortunately, as it turned out, Angela Merkel then chose not to follow his advice and Greece remained in the Eurozone. The “self-criticism” came in 2018, when the protagonist of that period was now president of the Bundestag. “I thought rather early to propose Greece’s exit from the euro, because I thought the Greeks would be more tolerant of a sudden shock than multi-year austerity programs.”, Schäuble told the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. In 2019, in the Financial Times, he again argued that Greece should not have joined the Eurozone in the first place and revealed that in 2015, when the chancellor did not follow his suggestion, he had considered resigning. His title “architect of austerity” about Europe, however, he said that he did not want him. “I only believed that monetary union could not exist without greater integration and common rules within the EU”he countered.

“I feel lonely”

The CDU’s defeat in the 2021 election brought both the end of his term as president of the Bundestag and his announcement that he did not intend to run for parliament again. The epilogue of his political life was to coincide with the end of his life, after a battle with cancer. “I feel lonely. There is no one left of my generation. But I can now see how I am going towards the end. I find it fascinating to watch myself”he had said in his last interview with the magazine Der Spiegel, a month ago. In his three-hour meeting with the journalist, he talked more about the past. History will surely judge this past. Along with his public life, History may also take into account that, those who knew him or worked with him, they always spoke of a naturally noble man, a dear colleague, a deeply philosophical statesman and a strong personality, whose tragic features were always present.

Source :Skai

With a wealth of experience honed over 4+ years in journalism, I bring a seasoned voice to the world of news. Currently, I work as a freelance writer and editor, always seeking new opportunities to tell compelling stories in the field of world news.